personal data

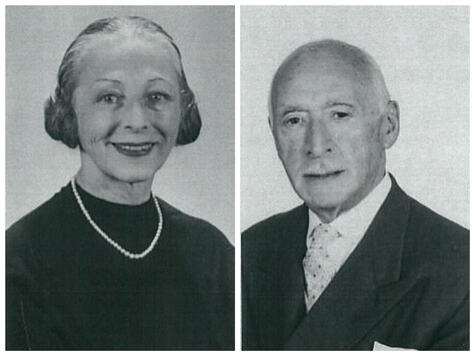

Bock Ida

Parents: Hermann Simon Rosenau and Luise née Feuchtwanger

Siblings: Hermann Sigmund and Felicie verh. Wolff

Spouse: Julius Bock

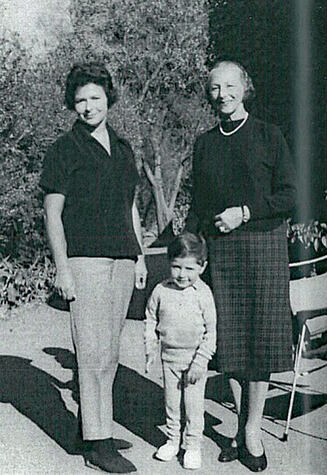

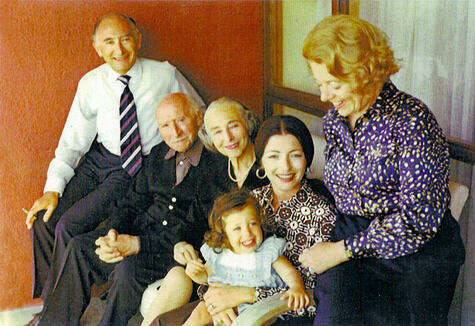

Children: Herbert Martin Meir, Kate Louise Leah m. Kallenbach

1933 emigrated to South Africa

biography

Ida Bock, née Rosenau came from a long-established Jewish family in Bad Kissingen whose roots can be traced back to the 18th century. It can’t be learned from the sources how long and in what periods of time Ida Bock lived in Bad Kissingen. She was born in Munich on December 4, 1893 as the daughter of the jeweler Hermann Simon Rosenau and his wife Luise, née Feuchtwanger. The family owned a jewelry shop and a residential home in both Munich and Bad Kissingen and spent the summer season in Bad Kissingen and the winter months in Munich.

In 1913, she married Julius Bock from Frankfort/ Main, who was 10 years her senior, in Munich. He came from a wealthy and respectable Frankfort family who belonged to the orthodox Breuer Congregation but was in no way narrow-minded but quite open-minded. Afterwards. Ida Bock lived in the city on the Main where in 1914, her son Herbert Martin was born. Her daughter Kate Louise was to follow in 1920 as her second child. Kate wrote a very personal family history in her later life which we owe a lot of information on the family to. Ida’s husband Julius worked in the Commodity exchange of the firm Mayer Bock that had been founded by his grandfather.

The Bock family lived in Blumenstrasse – not far away from Eschenheimer Tor. Ida’s daughter Kate remembers the atmosphere in her parents’ house: “We had a very large apartment – nine huge rooms plus an enormous enclosed big all glassed in Veranda, which we called the “winter garden”. It was full of palms and various other plants and we had breakfast and lunch there most of the year. One of the reception rooms, the Music Room, had a huge full size Bechstein Grand Piano, which nobody ever used. …We had a big household, a maid, a nanny, a cook, a cleaning woman. Also had a chauffeur, as neither Pepi nor Omi (that’s how Kate called her parents) could drive. The cook was Jewish because at that time we were still Kosher and no way could anybody not Jewish touch the food which we were about to eat. But in those days already, whenever Omi and Pepi went out to eat with their friends, they forgot about Kosher. (Kate L. Kallenbach, My memoirs – a letter to my son, Ch. 12, p. 20) My parents had a wonderful life. They had a huge circle of friends and were out most nights of the week or had dinner parties at home. They could seat 24 people round the dining-room table.” (Ibid. Ch. 5, p. 6) Ida Bock and her husband also often undertook holiday trips to Switzerland – to Wengen and St. Moritz – and to Italy, where Como, Stresa, Rapallo, Portofino and Venice belonged to their favourite destinations. In the summer, the family often met at the Mosler Municipal Swimming Pool on the River Main: “There Omi and Pepi met their friends. Pepi came from the office and I came straight from school. We all had lunch there.” Kate comments on the luxurious life not without some criticism:” So it was not surprising that they “lived it up” if they had the financial means. Certainly it is unlikely that they were very worried about the fact that there were millions of unemployed and a great depression. It would seem that none of them and all their Jewish upper-middle-class contemporaries had even an inkling or the slightest forewarning or could ever imagine what was in store for them in the very near future.” (ibid.)

The family also continued maintaining intensive contacts with Ida’s parents in Bad Kissingen. Ida’s daughter Kate regularly spent her summer holidays with her grandfather Hermann Simon Rosenau: “For me my grandfather was my hero. He took me for innumerable walks, especially in Kissingen into the woods looking for Lilies of the Valley, wild strawberries and champignons. … To this day my love for the meadows, full of flowers, and the woods, stems from that time. Even in the movies when I see woods or a meadow with flowers or even a tree lined street with autumn leaves, I think of Kissingen.” (Ibid. Ch. 8)

After the Nazi’s seizure of power, the situation abruptly changed. Ida’s husband Julius was no longer allowed to run his business as Jews were forbidden to do business at the Stock Exchange. As early as in December 1933, the Bocks sent their 19-year-old son Herbert to South Africa. A cousin of Julius Bock, who had become wealthy in South Africa, had conveyed a job for him in Port Elizabeth.

As the situation of the family continued to deteriorate, the rest of the family also made up their minds to leave Germany in 1934. There was “a dark cloud on the horizon. Seeing Pepi could no longer attend the Exchange, he could no longer earn a livelihood and it was Omi who decided that it would be the best for us also to emigrate. Herbert being in South Africa, it was logical for us to also immigrate there.” (Ibid. Ch. 16, p. 27) Kathe remembers how her mother prepared her for it. “One day Omi said to me ‘how would you like to live in a place where it is mostly sunny and beautiful beaches and you can swim in the sea’. So I answered that ‘I am very happy here and I don’t want to go anywhere to swim in the sea’. But there was no choice for me. The decision had been made. Omi decided not to tell anyone at all that we were leaving. She was much too afraid that it would leak out and that there might be difficulties. She wrote dozens of letters to innumerable friends and relatives, which she posted on the day we left. I was also not allowed to tell anyone at school and just didn’t show up again the day after we left.

At that time already, you could not just get up and go. There were all kinds of restrictions. One was not allowed to take any money whatsoever and I remember that Pepi had a Letter of Credit which he cashed in Basel, Switzerland. I have no idea what the sum was, but I do remember that both Omi and Pepi were very worried to get across the border from Germany to Switzerland at Basel without a hitch. I still remember how the border guard searched us and even opened Omi’s umbrella. I don’t know what he expected to find there, but perhaps he thought we had a gold bullion hidden in there. Luckily all went off without a hitch and Pepi cashed his Letter of Credit.

From Basel we went by train through Switzerland/ Italy to Genoa, which was the port of embarkation for the Italian Line to Cape Town. We sailed on the Dulio, a beautiful white boat. I loved the boat trip. I don’t remember when we embarked, but we arrived in Cape Town on Saturday, December 22, 1934. (Ibid. ch. 16, p, 28) When we arrived in the harbor, Ida’s daughter refused to disembark. “At that time I was still very “fromm” (Orthodox) – the direct influence of the religious Jewish school I had attended. As you know, if you are Orthodox you can’t ride on a Saturday but perforce you can travel on a ship, provided you don’t embark or disembark on a Saturday. As our boat docked on Saturday and (father’s cousin) Martin Hammerschlag met us at the dockside by car, it took Omi and Pepi more than an hour to persuade me to get off the boat. The only way they succeeded was because the boat left the same day for Durban. The performance started all over again when I had to get into Martin’s car. I was going to walk. I don’t know where I was going to walk to, but I was going to walk!” (Ibid. Ch. 17, p. 29)

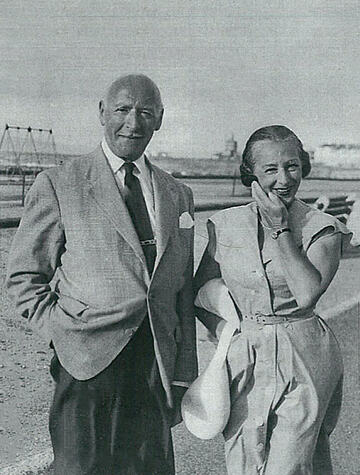

The following years were difficult for the family who lived in very modest circumstances in Cape Town. After Ida’s husband had first accepted a job for 10 pounds per month and she herself worked as a shop assistant in a textile business, Julius became a business partner in a perfume shop which had to close after a short time. After that Ida’s husband and her son Herbert opened the firm “Julius Bock & Son” together with her, an international commercial agency that provided its customers in South Africa with goods from all over the world. During the war years, the economic situation was difficult because at that time no goods from countries taking part in the war could be imported. After the war, however, the commercial agency developed into a prospering enterprise. Ida Bock also contributed to setting up the firm and managed a great deal of the business correspondence with foreign partners in those initial years.

What weighed heavily on her in those days was the uncertainty of the fate of her parents and her siblings who had emigrated to France already in 1933 but had been exposed to Nazi terror after the German invasion of France once again. Her father Simon Hermann, his wife Paula and Ida’s brother Hermann had fled to Nice because of that. When German troops also occupied the south of France after the landing of the Allied Forces in North Africa, mail contact which had been very lively till then stopped completely. “It was a terrible time. Omi was beside herself with worry and the worst thing was the uncertainty and the fact that one was absolutely powerless to do anything. …Omi never found out whether they were alive or what had happened to all of them. It was just too terrible for her. I can’t remember how long it took until eventually she got the bad news from the Red Cross that they had been deported to Auschwitz/ Oświęcim Extermination Camp in 1943. She couldn’t find out what had happened to them or whether they were still alive, which was terrible for her. (Ibid., ch. 10) “It was only long after the war ended that my mother heard from the Red Cross that they actually perished in the Camp.” (Ibid.)

From 1948, Ida Bock and her husband regularly travelled to Europe again and visited Ida’s sister Felicie Wolff in Paris for several weeks. She had survived the Nazi Era first in France and then in Switzerland with her family.

The Bock family lived in Bramley, a suburb of Johannesburg. Ida Bock rejected – according to what her daughter wrote – the Apartheid Policy of the South African Government and sympathised with Nelson Mandela, the leading representative of the country’s liberation movement whom she anonymously supported by means of a monthly donation. According to her daughter’s impression, the majority of the English-speaking South Africans were critical of the government, but only a minority intended to do something against it as it was very dangerous. (Ibid. ch.30)

Ida Bock died in March 1976 at the age of 82, few months before the decisive phase of the liberation movement in South Africa started with the Soweto Uprising. Her husband Julius had already died one year earlier. The two of them had been married for 61 years.

References

Datenbank Genicom![]()

Frankfurter Jüdisches Adressbuch 1935, S. 21![]()

Google Search zu Julius Bock mit Hinweis auf Geburtsdatum und Geburtsort bei Ancestry![]()

Hans-Jürgen Beck, Kissingen war unsere Heimat, S.671

Mitteilung Gary Kallenbach (Enkel Ida Bocks) an Ehepaar Ahnert, Mail vom 19.04.2020

Kate L. Kallenbach, My memoirs - a letter to my son

Photo credits

© Gary Kallenbach

Back